Forging Innovative Criminal Justice Solutions

- rebeccabromwich

- Jul 28, 2025

- 5 min read

An Arctic Example

Social Enterprise Fusing Together Social Justice and Crime Prevention

Rebecca Jaremko Bromwich

By fusing together restorative justice and micro-enterprise, communities can ensure that accountability is not the end point—but the starting point for opportunity.

This blog post presents one Arctic example of such an endeavour.

I have written elsewhere about the crossover from child protection to criminalization, arguing at least part of the solution to reducing crime lies in the child welfare system. In this blog, I argue that, similarly, at least part of the solution to criminal law issues - and specifically the overincarceration of Indigenous youth, comes from business innovation.

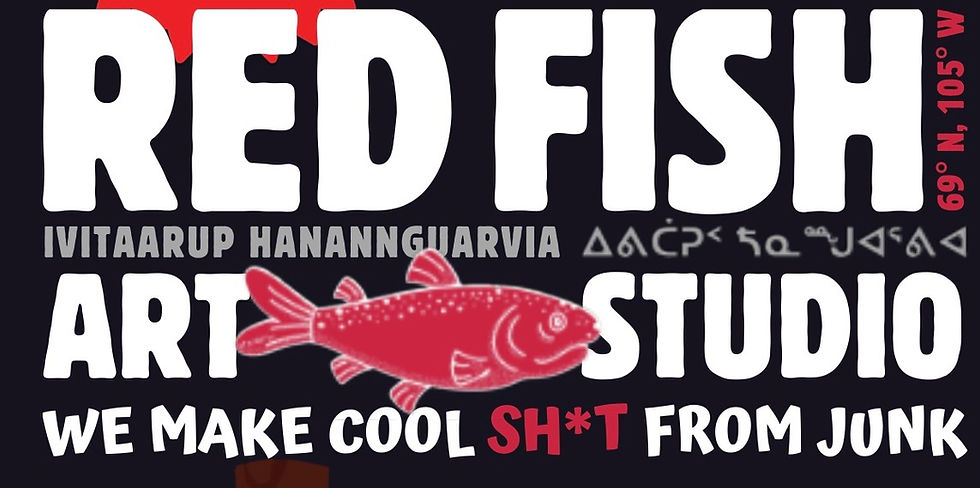

In Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, Redfish Art Studio is putting the idea of fusing social justice and business innovation together—literally—by helping at-risk Inuit youth, many with contact with the criminal justice system, gain employable welding skills and transition into paid work in their own communities. When meaningful employment, culture, and community accountability come together, the results can complement restorative justice processes and reduce the cycle of re-offending that continues to burden northern communities and the broader Canadian justice system. Evidence from national and territorial justice initiatives shows that culturally grounded, community-based programming linked to real economic opportunity is a critical missing link in efforts to address Indigenous overrepresentation in the criminal system.

Indigenous peoples—Inuit included—remain starkly overrepresented at every stage of Canada’s criminal justice system, from victimization through to custody. Federal justice data continue to document this long-standing pattern and emphasize that system-level reforms alone have not closed the gap. Structural factors—poverty, housing precarity, intergenerational trauma, and limited access to culturally safe services—feed into contact with police and courts. Without targeted, community-led interventions that address the social and economic roots of offending, traditional criminal processes risk recycling harm.

Nunavut’s Restorative Justice Diversion Program relies on Community Justice Committees (CJCs) that bring together offenders, victims, Elders, and local representatives to repair harm, restore relationships, and realign behaviour with Inuit societal values. Diversion can occur pre-charge or post-charge and is widely viewed as a constructive alternative for youth and lower-level offending. Yet community reports and territorial reviews note recurring practical challenges: uneven resources, volunteer fatigue, and limited post-diversion supports—especially employment pathways—that help participants stabilize their lives after community accountability processes conclude.

Redfish Art Studio started as a community arts workspace—shared tools, salvaged materials, mentorship from local craftspeople. It has since evolved into a social enterprise trades incubator: youth referred by Community Justice Committees, schools, or probation workers spend structured time in the studio learning safe tool use, basic carpentry, small-engine repair, and fabrication of functional art pieces (sled components, carving displays, modular storage for community halls). Graduates can ladder into paid project crews that take on local contracts—repairing municipal fixtures, building stage sets for cultural events, or producing small-batch furniture for regional sale. By aligning training with actual revenue-generating work, Redfish builds a bridge between restorative accountability and long-term employability—precisely the sort of 'solutions economy' approach social enterprise advocates have long urged Indigenous communities to adapt to local strengths.

Employment is one of the strongest predictors of successful reintegration after justice involvement. Canada’s Federal Framework to Reduce Recidivism highlights education, job skills, and supportive networks as core pillars for preventing re-offence. Comparable provincial corrections initiatives show that when people in custody (or community supervision) gain practical, marketable skills, they are more likely to secure work, rebuild confidence, and contribute positively to community safety. Translating that insight to the North means building employment pipelines that function in small, remote communities and respect local cultural economies—exactly the niche Redfish occupies by combining art, trades practice, and micro-contracting.

Courts across Canada are mandated to consider Gladue factors—systemic and background circumstances and culturally appropriate alternatives—when sentencing Indigenous offenders, including youth. Yet national reviews and northern commentary alike point out that Gladue’s promise often stalls without concrete, community-based options to recommend to courts. Programs like Redfish provide exactly the type of grounded alternative that Gladue writers, counsel, and judges can point to: a culturally anchored, skill-building placement that responds to the social roots of offending rather than defaulting to carceral or probation-only outcomes. Critiques that Gladue has not yet delivered transformative change underscore the need for more—and better resourced—community solutions of this kind.

Local justice workers report that youth who complete the Redfish skills block and accept short-term studio placements are showing higher school re-engagement and improved compliance with diversion agreements. While longitudinal recidivism data are still being gathered, early qualitative feedback from Community Justice Committee members and probation officers suggests that structured work, paycheques, and visible community contributions strengthen accountability and pride—protective factors noted in broader Indigenous justice program evaluations. Embedding Elders in the shop for cultural teaching days has further deepened relationships between youth and community mentors, reinforcing the restorative dimension that diversion aims to achieve.

Redfish Art Studio is not a silver bullet; no single community program can undo generations of colonial policy or the structural inequities that criminalize poverty. But it models a scalable idea: pair restorative justice with viable micro-enterprise so that accountability is matched with opportunity.

For policymakers, funders, and law schools working in partnership with northern communities, supporting hybrid models—part training centre, part business—may yield better long-term public safety outcomes than investing solely in downstream justice processing. As climate, cost of living, and demographic pressures intensify across the Arctic, communities need justice solutions that also create jobs.

Redfish shows how one small studio can spark that shift. Communities across Canada need more work like they are doing.

Key Justice Data in Nunavut and Canada (Selected)

Indicator | Nunavut / Inuit Youth | Canada (National Average) |

Incarceration Rate (per 100,000) | 800+ (adults); much higher among Inuit youth | 38 (youth); 85 (adults) |

Recidivism Rate (youth) | ~60% (estimate) | ~40% |

Restorative Diversion Participation | 60+ communities engaged with CJCs | Variable by province |

Youth Employment Post-Diversion | Improving with targeted programs (e.g., Redfish) | Data scarce; programs uneven |

Sources: Statistics Canada, Department of Justice Canada, Government of Nunavut, academic program reviews.

Written by Dr. Rebecca Jaremko Bromwich, a founding Board member of Redfish Art Studio.

References:

Canada, Department of Justice, Indigenous Overrepresentation in the Criminal Justice System: Causes and Responses (Ottawa: DOJ, 2021), online: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/jr/jf-pf/2021/jan02.html.

Nunavut, Department of Justice, Restorative Justice Program Annual Report 2022–2023 (Iqaluit: Government of Nunavut, 2023), online: https://gov.nu.ca/justice/documents-publications.

Canada, Office of the Correctional Investigator, Annual Report 2022–2023 (Ottawa: OCI, 2023) at 16–22, online: https://oci-bec.gc.ca.

Myrna McCallum, “Justice on the Land: How Community-Based Alternatives Can Rebuild Trust” (2020) 55:2 Canadian Lawyer 22.

Nicole E. J. Myers, “Gladue and Bail: The Precarious Liberty of Indigenous Accused” (2019) 46:3 Manitoba Law Journal 89.